BRYN CELLI DDU is a prehistoric site on Anglesey located near Llanddaniel Fab and has the honour of being Wales’ oldest monument.

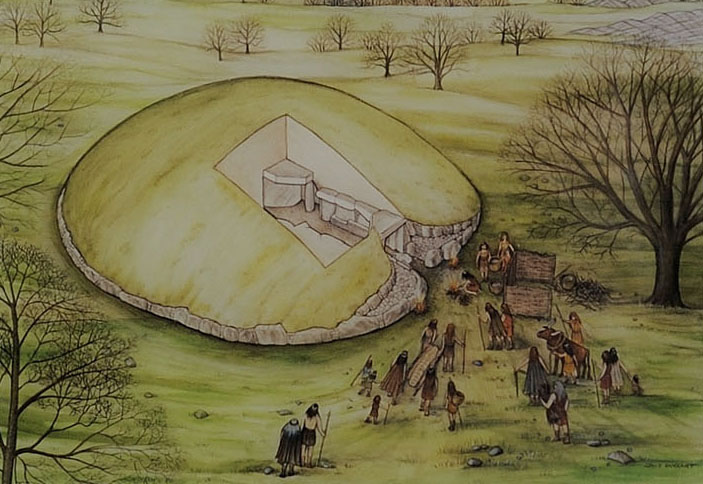

Visitors can get inside the mound through a stone passage to the burial chamber, and it is the centrepiece of a major Neolithic Scheduled Monument in the care of Cadw.

The presence of a mysterious pillar within the burial chamber, the reproduction of the ‘Pattern Stone’, carved with sinuous serpentine designs, and the fact that the site was once a henge with a stone circle, and may have been used to plot the date of the summer solstice have all attracted much interest.

Its name means ‘the mound in the dark grove’ and it was archaeologically excavated between 1928 and 1929.

This site was developed in several stages. The earliest noticeable part is the henge, a ritual enclosure marked by a ditch, 21m in diameter.

It would originally have been surrounded by a bank, which has now mostly disappeared.

A circle of standing stones was enclosed within the boundary. This type of structure is similar to other henges known from the late Neolithic period, about 3000 BC.

Cremated human remains were found buried at the base of some of these stones. This henge may have been preceded by another ritual structure. A row of postholes within the henge was uncovered during excavations in 1928.

Charcoal found in the bottom of these was carbon dated to the Mesolithic period, much older than the henge.

At some point during the henge’s period of use a pit, about 1m in diameter, was dug at the centre of the henge, through the grass that had covered the site. A fire had been built in the pit and a burnt human ear bone and some wood pieces were found in the pit.

The pit was then filled in and covered with two large slabs of stone (more on these later).

About 1000 years after the henge was built, near the end of the Neolithic, the site went through a complete redesign.

The standing stones that originally formed a circle within the henge were knocked over and damaged, perhaps by the builders of the next phase.

Some stones were broken where they lay, by having large stones dropped on them. It’s been suggested that the deliberate destruction of these stones was a result of a conflict between peoples of two religious beliefs, and the later culture was destroying evidence of the previous one, rather than reusing the stones.

A passage tomb was then built within the boundaries of the old henge. This consisted of a long passage, about 8m in length, leading to a polygonal stone chamber, 3m across at its widest.

The chamber was capped by one large stone, plus another smaller one. The passage was divided into two parts, an inner passage roofed with large capstones, plus a shorter outer one which was never roofed.

The tomb was apparently sealed after funerals by filling in the outer passage with soil and stone. The presence of human bone fragments in this infilling suggests that it was deliberately filled, rather than just material collapsing into there later.

A circle of kerbstones was built around the structure, following the line of the original ditch of the henge. These formed a wall around the perimeter of the mound covering the passage and chamber.

The passage is aligned so that the rays of the sunrise on the summer solstice light up the passageway; it is the only passage tomb on Anglesey with such a distinctive alignment.

It was mentioned above that the pit in the centre of the henge had been covered by two stones. When the monument was excavated in 1928 one of the stones was raised to reveal a complex pattern of carvings.

The carvings, composed of spirals and zig-zags in a maze-like pattern, cover both sides, as well as across the top. The individual carved lines continue from one side to the other over the top.

The carving clearly shows it was meant to be standing, and the excavation shows that it was deliberately placed on top of the pit and didn’t just fall over, so it seems that this was part of the earlier henge period of the monument. Perhaps it was another victim of the desire of a new religious culture to obliterate the symbols of the previous one.

The patterned stone was a coarse gritstone, which would deteriorate when exposed to the weather, so it was sent to the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff for safekeeping and study. A cast of the stone was returned to Bryn Celli Ddu, to be erected at the spot where it most likely originally stood.

Bryn Celli Ddu was first mentioned in a publication by Henry Rowlands, in his book Mona Antiqua Restaurata, in which he notes two adjacent monuments (one now disappeared) with three flat table stones and several uprights.

By the time Thomas Pennant visited it in 1770, as mentioned in his Tours in Wales, the crawlspace inside had been explored, the pillar was described and he notes that human bones were found that “crumbled at the touch”.

John Skinner was the next to describe it and other monuments on Anglesey, in his 1802 Ten Days’ Tour Through the Isle of Anglesea. He spoke to local labourers who had been employed to reuse the stones for walls.

They told stories of a gold object having been found, but also of a spirit in white guarding the tomb. The farmer who first encountered the spirit returned later, in the hope of finding treasure, only to find that the “spirit” was actually the upright pillar.

Skinner himself also entered the tomb, describing the pillar and other stonework in greater detail than previous accounts.

Further details are given in an article entitled Cromlech at Bryn Celli Ddu, Anglesey, in Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1847, in which the unknown author says the interior chamber had been ransacked and the central pillar toppled.

However, the landowner had by this time taken steps to fence off the monument and preserve the site. The etching of the cromlech to the left comes from this article.

The 1869 publication by Rev. E.L. Barnwell, Cromlechs of North Wales, describes the first proper excavation and mapping of the site, with a diagram showing the positions of the stones of the passage and chamber.

Excavation of the site revealed fragments of lead and charcoal, a broken flint knife, a javelin head, and some human bones. No pottery was found.

Neil Baynes’ 1912 article Megalithic Remains of Anglesey gives a good overview of the monument, but also includes the first photographs of it.

By this time trees that had been planted near it had become very large and were growing up between the stones, placing the tomb at risk. Baynes suggested that the landowner, Lord Anglesey, should turn the site over to the Commissioners for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments, which he did in 1923.

Following on from this, work was begun to carefully remove the trees and stabilize the stones, which were now balanced very precariously.

The passage and chamber, which had become filled with soil, were excavated. The tomb was then meticulously examined and described by W. Hemp and his team, with the results published in the 1930 paper The Chambered Cairn of Bryn Celli Ddu.

Once the site was fully examined and the stones stabilized the whole chamber was again buried under a mound, to protect the stones as well as to make it into a place of public interest that resembles the original structure.

The original mound would have filled the entire area within the henge boundaries, with the chamber in the centre. However, the current mound only just covers the passage and chamber.

This allows the back wall of the chamber to remain exposed so that light can illuminate the interior of the chamber, letting those who venture inside to appreciate it without the need for torches.

Add Comment