WHILST you probably know the names of Tesla and Edison for their work with electricity, it’s highly likely you may never have heard of the name Sir William Robert Grove, a Welsh physicist who was a pioneer of fuel cell technology.

Born in Swansea in 1811, his early education was in the hands of private tutors, before he attended Brasenose College, Oxford to study classics, though his scientific interests may have been cultivated by mathematician Baden Powell.

It was love that ultimately set him on his scientific path ultimately however.

In 1829 at the Royal Institution Grove met Emma Maria Powles and he married her in 1837. The couple embarked on a tour of the continent for their honeymoon and this sabbatical offered Grove an opportunity to pursue his scientific interests and resulted in his first scientific paper suggesting some novel constructions for electric cells.

Put your lab coat on, because this is going to get scientific.

During 1839, Grove developed a novel form of electric cell, the Grove cell, which used zinc and platinum electrodes exposed to two acids and separated by a porous ceramic pot.

Grove announced the latter development to the Académie des Sciences in Paris in 1839, and in 1840 Grove invented one of the first incandescent electric lights, which was later perfected by Thomas Edison.

Later that year he gave another account of his development at the British Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in Birmingham, where it aroused the interest of Michael Faraday. On Faraday’s invitation Grove presented his discoveries at the prestigious Royal Institution Friday Discourse on 13 March 1840.

Grove’s presentation made his reputation, and he was soon proposed for Fellowship of the Royal Society.

As soon as he became a Fellow he was a critic of the Society, deprecating its cronyism and the de facto rule of a few influential Council members.

In 1843, he published an anonymous attack on the scientific establishment in Blackwood’s Magazine and called for reform. In 1846 Grove was elected to the Council of the Royal Society, and was heavily involved in the campaign to modernise its charter, in addition to campaigning for the public funding of science.

Grove also attracted the attention of John Peter Gassiot, a relationship that resulted in Grove’s becoming the first professor of experimental philosophy at the London Institution in 1841.

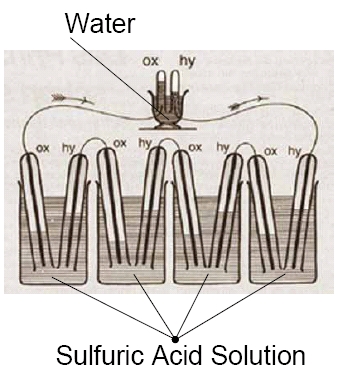

In 1842, Grove developed the first fuel cell (which he called the gas voltaic battery), which produced electrical energy by combining hydrogen and oxygen, and described it using his correlation theory.

In developing the cell and showing that steam could be disassociated into oxygen and hydrogen, and the process reversed, he was the first person to demonstrate the thermal dissociation of molecules into their constituent atoms.

The first demonstration of this effect, he gave privately to Faraday, Gassiot and Edward William Brayley, his scientific editor.

In 1846, Grove published On The Correlation of Physical Forces in which he anticipated the general theory of the conservation of energy.

From 1846 Grove started to reduce his scientific work in favour of his professional practice at the bar, his young family providing the financial motivation, and in 1853 became a QC.

The bar provided him with the opportunity to combine his legal and scientific knowledge, in particular in patent law and in the unsuccessful defence of poisoner William Palmer in 1856.

He was especially involved in the photography patent cases of Beard v. Egerton (1845–1849), on behalf of Egerton, and of Talbot v. Laroche (1854). In the latter case Grove appeared for William Fox Talbot in his unsuccessful attempt to assert his calotype patent.

Grove also served on a Royal Commission on patent law and on the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers.

In 1871 he was made judge of the Court of Common Pleas, and was appointed to the Queen’s Bench in 1880. He was to have presided at the Cornwall and Devon winter assizes of 1884, which would have entailed him trying the notorious survival cannibalism case of R v. Dudley and Stephens.

However, at the last minute he was substituted by Baron Huddleston, possibly because Huddleston was seen as more reliable in ensuring the guilty verdict that the judiciary required.

Grove did sit as one of five judges on the final determination of the case in the Divisional Court of the Queen’s Bench.

Grove has been described as: “A careful, painstaking and accurate judge, courageous and not afraid to assert an independent judicial opinion. However, he was fallible in patent cases, where he was prone to become overinterested in the technology in question and to be distracted by questioning the litigants as to potential improvements in their devices, even going so far as to suggest his own innovations.”

He retired from the bench in 1887.

Add Comment