HE’S known as the father of the NHS, a visionary for his time, and an extremely controversial figure for most who butted heads with him in Parliament – including Winston Churchill.

But, over 70 years on, the NHS survives as one of the UK’s greatest achievements, and we can thank a Welshman for the service.

So who was Aneurin Bevan?

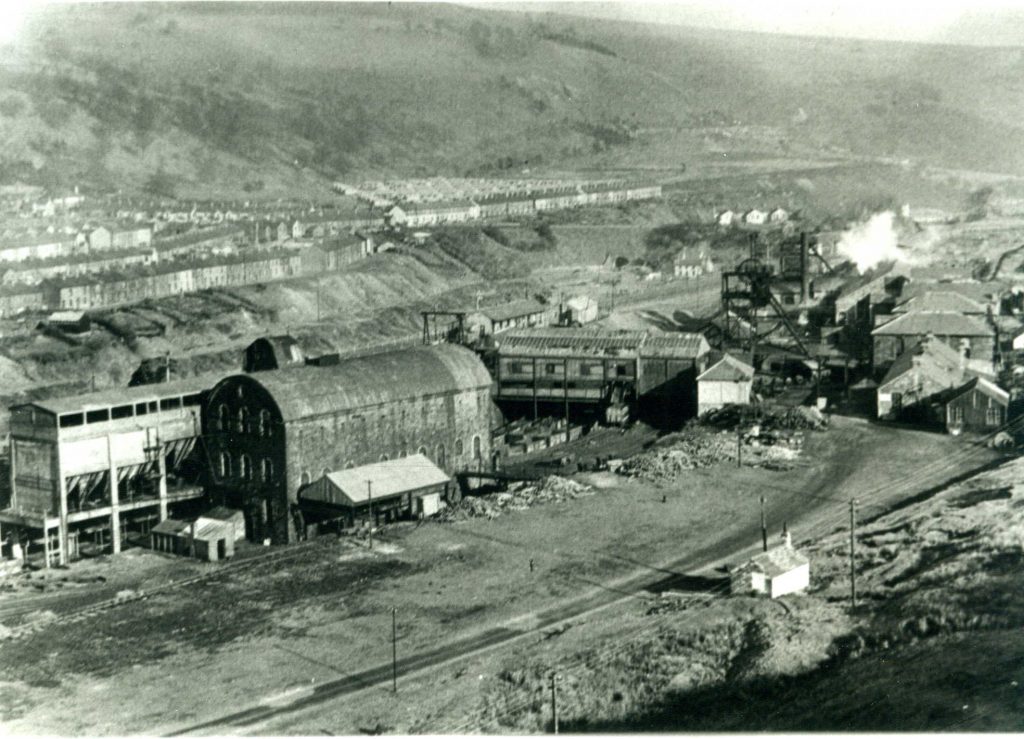

Aneurin Bevan was born in Tredegar in 1897 into a large mining family.

Two thirds of the adult males in the town worked underground for the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company, and in November 1911, the month he turned fourteen years old, Bevan followed his father and elder brother down the pit.

He started working in the Ty-trist Colliery, all the while spending as much time as he could in the Tredegar Workmen’s Institute Library, devouring the works of – among many other writers – Rider Haggard, Jack London and H.G. Wells.

Funded by the South Wales Miners’ Federation, Bevan spent two years studying economics, politics and history at the Central Labour College in London. He discovered Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, solidifying his left-wing political outlook.

In 1919 he moved to London to spend two years studying economics, politics and history at the Central Labour College, where his reading widened to embrace Marx and Engels, and after returning to Wales there followed years during which, for the most part, he was unemployed.

His father, with whom he regularly spent hours discussing his political aims and the means of achieving them, died in his arms of the miners’ disease pneumoconiosis in 1925.

The strike brought Bevan to the fore as a leader of the South Wales miners, and he orchestrated the distribution of strike pay in Tredegar during the six months lock-out the miners endured after the industrial action.

He became a councillor on Monmouth County Council in 1928, then a member of parliament for Ebbw Vale in 1929. His maiden speech was an attack on Winston Churchill, who he saw as the main enemy of the miners.

Bevan married a fellow left-wing Labour MP, Jennie Lee, in 1934 and together they campaigned to support the Socialists in the Spanish Civil War against Franco as well as setting up the Committee for the Relief of the Victims of German Fascism.

In 1936 a group of prominent left-wingers including Bevan set up a weekly Socialist newspaper, The Tribune, followed by trips around Spain during the Civil War. His activism and agitation led to his brief expulsion from Labour in 1939, but he agreed to toe the party line and was readmitted.

Despite opposing Churchill in mining matters, Bevan argued that he should replace Neville Chamberlain as prime minister. But once Winston Churchill was in power, Bevan criticised the wartime reductions in civil liberties.

In 1945, the general election saw Labour returned comprehensively to government. Bevan saw this post-war victory as a chance to implement radical social reform.

Then in 1948 the National Health Service Act, which Bevan had seen through Parliament, became law. This allowed for people to receive, free at the point of use, medical diagnosis and treatment at home or in hospital, and in addition dental and ophthalmic treatment.

Brian Brivati observed: “Bevan was now in charge of 2,688 hospitals in England and Wales. It was the decision to nationalise the hospitals that made the profound difference in the structural change brought about by the creation of the NHS.

“This decision was Bevan’s and its implementation was down to his skill, patience, and application as a minister.

“It is the most significant and lasting reform in the history of the Labour party and it was achieved by one man. The survival of the NHS is testament to Bevan’s ability and vision as a minister…”

The idea of an NHS paid for almost exclusively by the taxpayer has so deeply penetrated our national psyche that it is worth remembering that it was not inevitable.

The most obvious alternative was one based on compulsory national health insurance.

This principle had been established by the Lloyd George reforms at the beginning of the century and was the model endorsed by the Beveridge report, the foundation of most postwar welfare reforms.

Labour welcomed the Beveridge report on its publication.

But Bevan had always opposed the contributory principle. He thought that a free health service should be accompanied by a redistribution of wealth through the tax system.

Bevan’s way of proceeding was also in marked contrast with practice elsewhere. According to Rivett, “few other countries, outside the Eastern bloc, followed the same route” that Britain took.

Yet Britain embarked on an uninsured health service with apparently little debate about the principle involved, or its sustainability.

Bevan convinced the British people that the NHS was the best system in the world.

Following the creation of the NHS, there was almost immediately debate about what was meant by a “free health service.”

The issue of health service charges was to lead to Bevan’s resignation from the cabinet. His adversary was the new Labour chancellor, Hugh Gaitskell, who believed that Bevan had taken too far his idea of a free health service, that it should not extend to providing things like spectacles and false teeth which were not linked to illness, and that prescription charges were needed in order to suppress unnecessary demand.

The cabinet even considered charges for hospital stays.

At the time of his resignation, Bevan had failed to convince either the cabinet or the left wing of his party of the matter of principle which mattered enough to him to sink his own career.

In an extraordinarily bad tempered speech he increased resentment against him by referring to “my health service.”

According to Tony Benn’s diaries, “He shook with rage and screamed….The megalomania and neurosis and hatred and jealousy he displayed astounded us all.”

Such reports make it really quite surprising that it did become widely accepted that Bevan was the father of the NHS, that his resignation had been on an important matter of principle, and that a completely free service was the defining principle of the NHS.

In the years since Bevan, there has been an important development in Labour’s general political outlook which logically should have led it to rethink its stand on the NHS.

Labour has abandoned its commitment to redistributive taxation. We are thus left with a commitment to fund the NHS almost exclusively out of taxation, without any policy to increase the amount of tax available to pay for it.

The paradox is that the Bevan model has led to very tight restriction of health expenditure.

There has been little to choose between the political parties and over the years the treasury has kept the lid screwed down tightly, and the NHS has had nowhere else to turn for money.

The signs are that our low level of expenditure is not just a demonstration of our efficiency: Britain is actually spending too little on health.

In December 1959 an exploratory operation revealed the presence of cancer in his stomach. He returned to his Buckinghamshire home Asheridge Farm to recuperate, with every expectation to resuming a role in politics, but recovery was painfully slow.

Bevan never returned to the political mainstream. His health progressively deteriorated, and he died in his sleep at Asheridge on 6th July 1960. On the following morning a leader in The Times concluded:

“‘His gifts were great, not least his power to win friendship among political opponents. His purpose was sincere; and he fought for what he believed in, often to the detriment of his own fortunes. He was colourful figure in Parliament and, surprising as it may be to those who knew only the bogy-man image, a gay one.

“Bitterness he could show, but it was transient. Even the victims of his jibes on the opposite benches could as often as not appreciate their artistry. The House of Commons will be a greyer place now that he will no longer be there.”

Bevan’s ashes were scattered on the hills above Tredegar, and it was here that the Bevan Memorial Stones were unveiled by Michael Foot in 1972. The largest stone represents Nye himself, while the three smaller represent his constituency towns of Ebbw Vale, Tredegar and Rhymney.

Add Comment