ISAMBARD KINGDOM BRUNEL, it’s fair to say, connected Wales to much of the land around us.

Some say that Isambard Kingdom Brunel was the greatest railway engineer of his age – arguably, of any age, having built twenty-five railways lines, over a hundred bridges, including five suspension bridges, eight pier and dock systems, three ships and a pre-fabricated army field hospital.

Brunel was born at Portsea on April 9 1806 and from the start was destined for a career in engineering.

After working as an assistant engineer on his father’s project to dig the world’s first underwater tunnel, beneath the Thames in London – a project that severely injured and very nearly killed him – Brunel looked west.

In 1833 he was appointed chief engineer of the Great Western Railway but he had greater aims than simply constructing the line from London to Bristol. His idea was to extend the line into Wales from where it would provide a much-needed link to both Ireland and New York.

Brunel’s intention was to create and run the South Wales Railway from Gloucester to Abermawr near Fishguard where he would build a terminus and sea port, thus neatly connecting London with New York.

The Severn Tunnel was not then in existence and so Gloucester, which could be reached via the Great Western Railway, was the logical place to begin the new railway.

Great Western Railway contributed £600,000 towards the projected project cost of over £2 million but Brunel, with his passion for careful surveys and routes – not to mention his preference for the broad gauge system, 7ft ¼in as opposed to the 4ft 8½in of the standard gauge – was always going to incur excess expense.

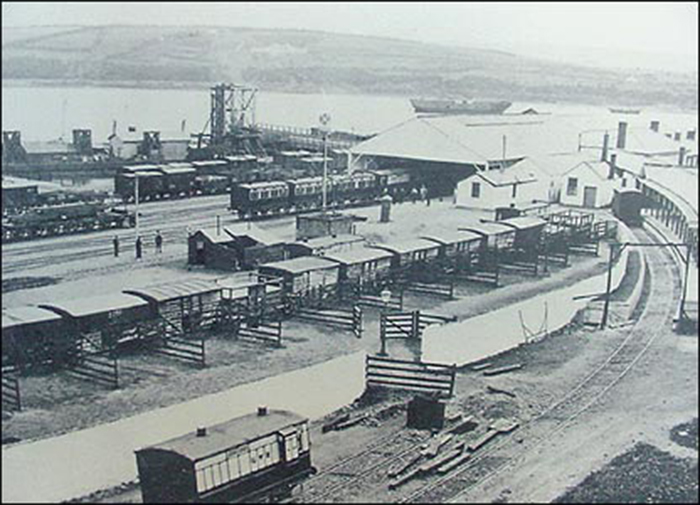

Consequently, due to financial difficulties, the plan was changed and the western terminus was built at Neyland (New Milford as it was called) on the Milford Haven waterway instead of Fishguard.

Although the line to the east of Swansea was open by the summer of 1850, the western section was not completed for another six years but, when it finally opened, the two railways – which merged in 1862 and altered their track to standard gauge 10 years later – at last provided a direct link between London and the west.

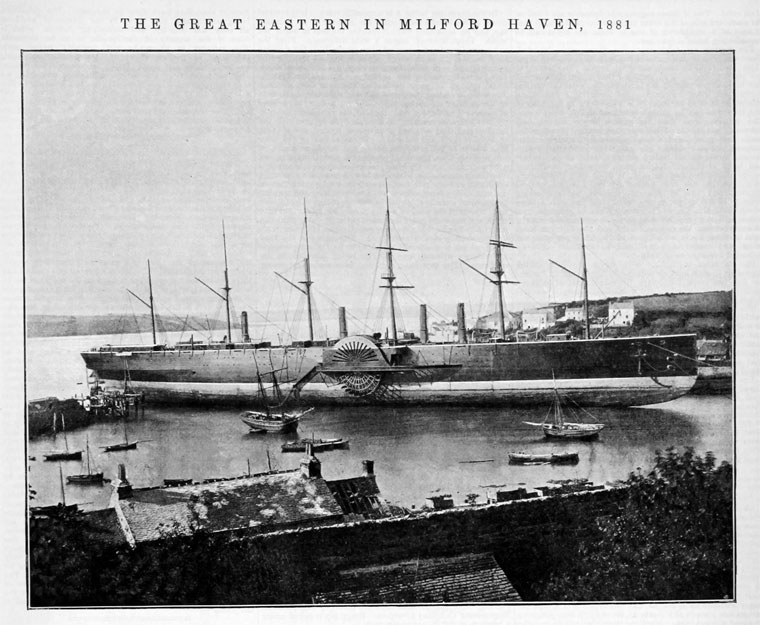

As Brunel had envisaged, the dock at Neyland operated ships for the route to both Ireland and the New World. Brunel’s most ambitious (and ultimately unsuccessful) ship, the gigantic Great Eastern, paid several visits to the place and was even laid up there for the winter of 1860. A road in the town is now named after her.

Although the dock and port at Neyland closed in 1906, transferring business to Fishguard, as Brunel had always intended, the old port still has some connection with the man. Part of the guard rails above the waters of Milford Haven were made out of Brunel’s broad gauge track, proving, if nothing else, the long life and durability of the system.

There are many other Brunel connections in Wales. Notable among them is the bridge across the Wye at Chepstow, a construction raised on large cast iron piers. There is also the 37 span viaduct over the River Tawe at Landore in Swansea, the longest timber viaduct he ever built.

One of Brunel’s most fascinating creations was the series of flying arches – just like flying buttresses on cathedrals – across the track at Llansamlet. Their intention was to prevent the flanking embankments sliding down onto the track in times of heavy rain or inclement weather.

Brunel was a man of many parts and did not just work for the Great Western and South Wales railways.

He was also instrumental in designing the Taff Vale Railway, one of the main arteries for taking coal down the Rhondda to Cardiff. He was responsible for re-routing the River Taff away from what became known as Cardiff Arms Park, thus helping cure some of the drainage problems from which the area always suffered.

The stone viaduct at Goitre Coed, crossing the River Taff, remains one of his most beautiful creations.

In 1851 Brunel designed the Vale of Neath Railway and, as part of this project, built the Dare Valley Viaduct which took coal down the Cwmdare Valley. Sadly, the viaduct was dismantled just after World War Two in 1947.

In July 1857 Brunel visited Neyland and Milford Haven. There was intense speculation – and hope – that he was looking to design and create a port just for the Great Eastern, which was then under construction at Millwall.

In October of the following year he visited the area again, this time with his wife Mary, staying in the Lord Nelson Hotel in Milford.

Brunel’s health had been failing for some time before he had a stroke on board the SS Great Eastern. He was taken back to his home at 18 Duke Street, London where he died on 15 September 1859 at the age of fifty three.

He was buried in the family vault at Kensal Green Cemetery, London. Memorials were quickly raised, including the words ‘I K Brunel 1859′ being added to the portals at each end of the Royal Albert Bridge at Saltash which opened just a few months before his death.

This memorial can still be seen on the bridge today.

A man of great energy and skill, Brunel seems now to epitomise the Victorian entrepreneur. His connections with Wales are significant even though he himself was not Welsh. He undoubtedly had a major role in building the country that we see today.

Add Comment