OFFA’S DYKE may not make the same impression as the Great Wall of China, however this fascinating earthwork, possibly dating back thousands of years, is one of Wales’ most fascinating landmarks.

Following the border between Wales and England, the structure is named after Offa, the Anglo-Saxon king of Mercia from AD 757 until 796, who is traditionally believed to have ordered its construction.

Mercia dominated what would later become England for three centuries, subsequently going into a gradual decline while Wessex eventually conquered and united all the kingdoms into the Kingdom of England.

Although its precise original purpose is debated, it delineated the border between Anglian Mercia and the Welsh kingdom of Powys.

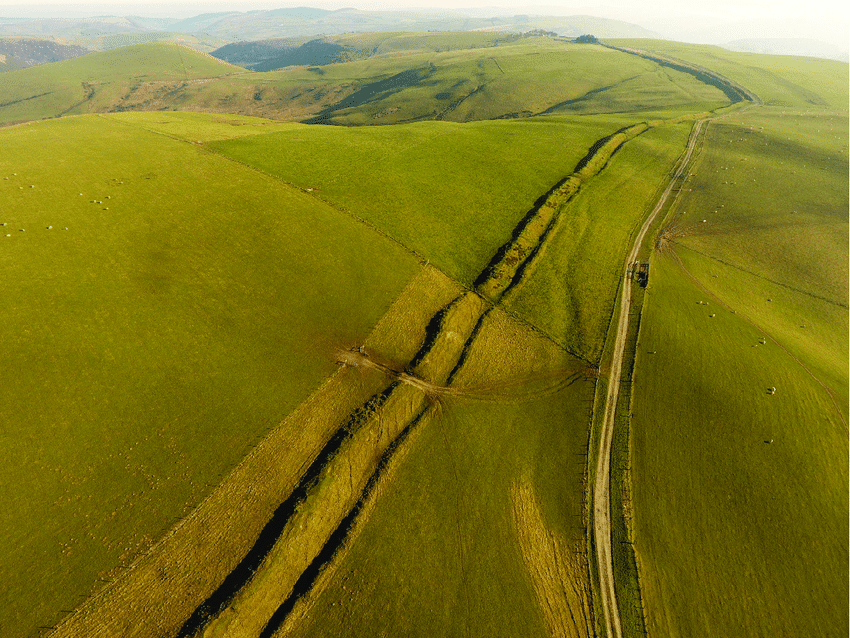

The earthwork, which was up to 65 feet (20 m) wide and 8 feet (2.4 m) high, traversed low ground, hills and rivers. Today it is protected as a scheduled monument.

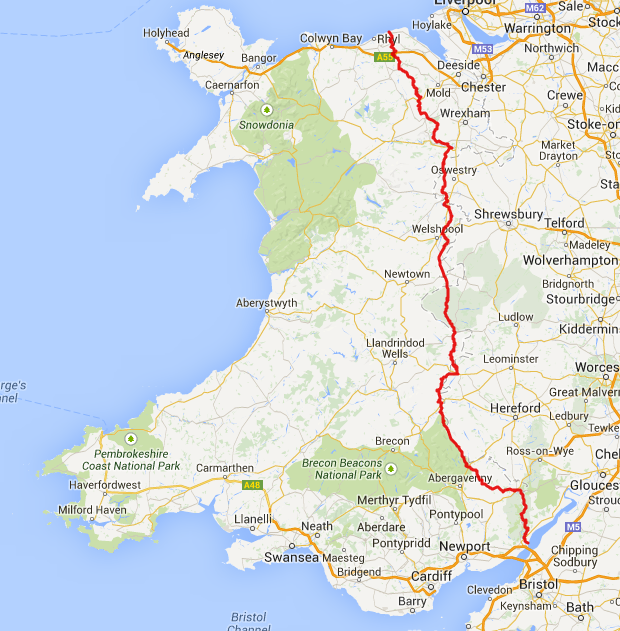

Some of its route is followed by the Offa’s Dyke Path; a 177-mile long-distance footpath that runs between Liverpool Bay in the north and the Severn Estuary in the south.

Although the Dyke has conventionally been dated to the Early Middle Ages of Anglo-Saxon England, research in recent decades – using techniques such as radioactive carbon dating – has challenged the conventional historiography and theories about the earthwork, and show that it was started in the early fifth century, during the sub-Roman period.

The generally accepted theory of the earthwork attributes most of its construction to Offa, King of Mercia from 757 to 796. The structure did not represent a mutually agreed boundary between the Mercians and the Kingdom of Powys.

It had a ditch on the Welsh (western) side, with the displaced soil piled into a bank on the Mercian (eastern) side.

This suggests that Mercians constructed it as a defensive earthwork, or to demonstrate the power and intent of their kingdom.

Throughout its entire length, the Dyke provides an uninterrupted view from Mercia into Wales. Where the earthwork encounters hills or high ground, it passes to the west of them.

Although historians often overlook Offa’s reign due to limitations in source material, he ranks as one of the greatest Anglo-Saxon rulers – as evidenced in his ability to raise the workforce and resources required to construct Offa’s Dyke.

The construction of the earthwork probably involved a corvée system requiring vassals to build certain lengths of the earthwork for Offa in addition to the normal services that they provided to their king.

The Tribal Hidage, a primary document, shows the distribution of land within 8th-century Britain; it shows that peoples were located within specified territories for administration.

The first historians and archaeologists to examine the Dyke seriously compared their conclusions with the late 9th-century writer Asser, who wrote: “there was in Mercia in fairly recent time a certain vigorous king called Offa, who terrified all the neighbouring kings and provinces around him, and who had a great dyke built between Wales and Mercia from sea to sea”.

In 1955 Sir Cyril Fox published the first major survey of the Dyke.

He concurred with Asser that the earthwork ran ‘from sea to sea’, theorising that the Dyke ran from the River Dee estuary in the north to the River Wye in the south: approximately 150 miles.

Although Fox observed that Offa’s Dyke was not a continuous linear structure, he concluded that earthworks were raised in only those areas where natural barriers did not already exist.

Sir Frank Stenton, the UK’s most eminent 20th-century scholar on Anglo-Saxon England, accepted Fox’s conclusions. He wrote the introduction to Fox’s account of the Dyke.

Although Fox’s work has now been revised to some extent, it still remains a vital record of some stretches of Offa’s Dyke that still existed between 1926 and 1928, when his three field surveys took place, but have since been destroyed.

In 1978, Dr Frank Noble challenged some of Fox’s conclusions, stirring up new academic interest in Offa’s Dyke.

His MPhil thesis entitled “Offa’s Dyke Reviewed” (1978) raised several questions concerning the accepted historiography of Offa’s Dyke.

Noble postulated that the gaps in the Dyke were not due to the incorporation of natural features as defensive barriers, but instead the gaps were a “ridden boundary”, perhaps incorporating palisades, that left no archaeological trace.

Noble also helped establish the Offa’s Dyke Association, which maintains the Offa’s Dyke Path. This long-distance footpath mostly follows the route of the dyke, and is a designated British National Trail.

John Davies wrote of Fox’s study: “In the planning of it, there was a degree of consultation with the kings of Powys and Gwent.

“ On the Long Mountain near Trelystan, the dyke veers to the east, leaving the fertile slopes in the hands of the Welsh; near Rhiwabon, it was designed to ensure that Cadell ap Brochwel retained possession of the Fortress of Penygadden.

“And, for Gwent, Offa had the dyke built “on the eastern crest of the gorge, clearly with the intention of recognizing that the River Wye and its traffic belonged to the kingdom of Gwent.”

Ongoing research and archaeology on Offa’s Dyke has been undertaken for many years by the Extra-Mural Department of the University of Manchester. Interviews with Dr David Hill, broadcast in episode 1 of In Search of the Dark Ages (aired in 1979), show support for Noble’s idea.

Most recently Hill and Margaret Worthington have undertaken considerable research on the Dyke.

Their work, though far from finished, has demonstrated that there is little evidence for the Dyke stretching from sea to sea.

Rather, they claim that it is a shorter structure stretching from Rushock Hill north of the Herefordshire Plain to Llanfynydd, near Mold, Flintshire, some 64 miles.

According to Hill and Worthington, dykes in the far north and south may have different dates, and though they may be connected with Offa’s Dyke, there is as yet no compelling evidence behind this. However, not all experts accept this view.

The England–Wales border still mostly passes within a few miles of the course of Offa’s Dyke through the Welsh Marches. A 3-mile section of the Dyke which overlooks Tintern Abbey and includes the Devil’s Pulpit near Chepstow is now managed by English Heritage.

All sections of Offa’s Dyke that survive as visible earthworks, or as infilled but undeveloped ditch, are designated as a scheduled monument. However, some parts of the Dyke may also remain buried under later development.

Some sections are also defined as Sites of Special Scientific Interest, including stretches within the Lower Wye Valley SSSI and the Highbury Wood National Nature Reserve. Parts are located within the Wye Valley and Shropshire Hills Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Most of the line of Offa’s Dyke is designated as a public right of way, including those sections which form part of the Offa’s Dyke Path.

In August 2013, a 45-metre section of Dyke, between Chirk and Llangollen, was destroyed by a local landowner. The destruction of the Dyke to build a stable was said to be like “driving a road through Stonehenge” but the perpetrator escaped punishment.

In 2010, the Dyke was proposed by the Offa’s Dyke Association and local authorities for World Heritage Site status.

Part of the proposal stated:

“Offa’s Dyke is a victim of its very scale, nature, meaning and historical success. It is located in two countries, six local authority areas, multiple ownerships and multiple land-use contexts.

“The main professional stakeholders – such as the English and Welsh path and heritage management agencies – are organisationally and functionally separate.

“The ancient monument is now often seen as secondary to the modern path, and heritage advice about individual dyke sections is not generally coordinated via any connected overview of the values of the whole monument.

“Moreover, despite the lasting legacy of Offa’s Dyke for English and Welsh communities alike, there is limited public awareness of the monument and its remarkable link to modern ideas of national identity.”

The proposal was rejected in 2011.

Add Comment