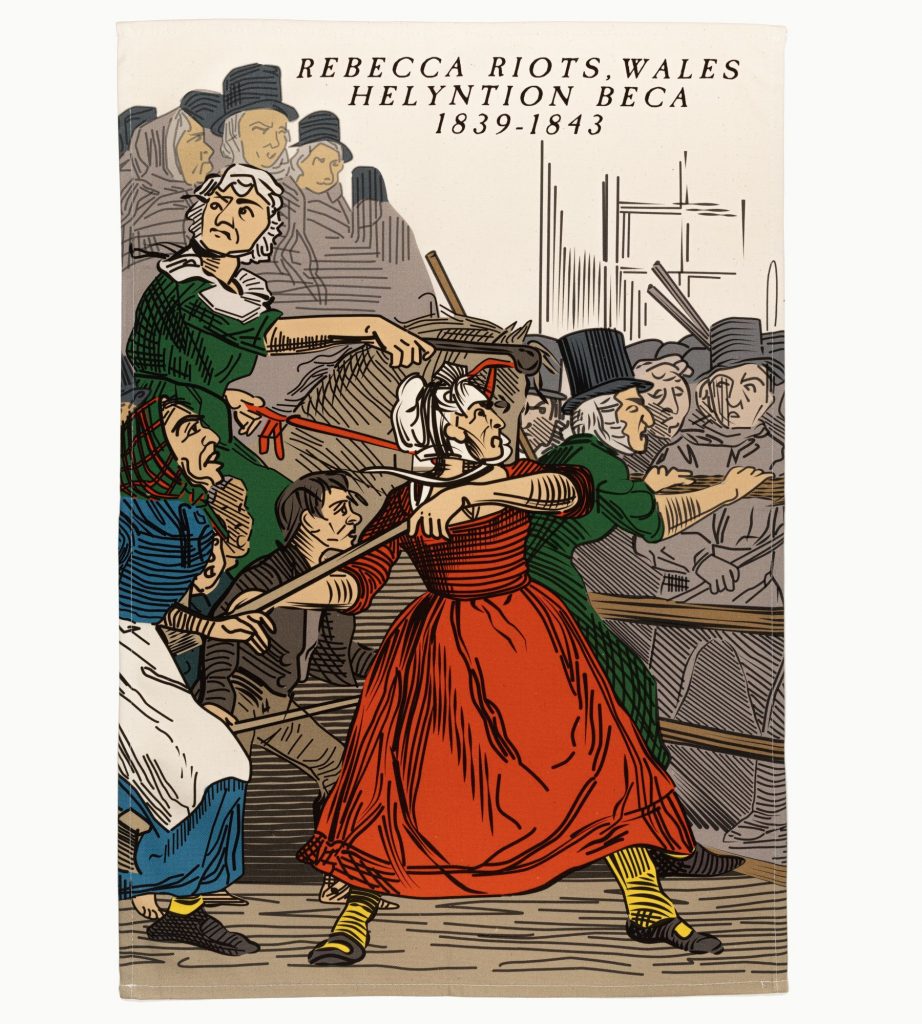

WITH the rights of protesters being debated by the police, government and media at the moment, it seems like the right time to look back at perhaps the most famous riots in Welsh history.

We are of course talking about the Rebecca Riots.

The Rebecca Riots were a series of protests against conditions in the rural areas of Wales between 1839 and 1843. They are usually seen as attacks on toll gates on the roads of Wales.

But many ‘Rebecca’ incidents – almost half – were about general economic conditions in the countryside and not about tolls at all.

The riots were mainly confined to Pembrokeshire, Ceredigion and Carmarthenshire; there was only one incident in north Wales at Penmorfa, near Porthmadog, in Caernarfonshire and this was really a joking re-enactment of the south-west Wales incidents.

Underlying the protests were the economic conditions of the time and the relationship between farmers and landlords, and the church.

The population of the rural areas of Wales had doubled in the century before the riots, despite the large numbers of people who left the countryside for the industrial areas of Wales and emigrated to America.

It was hard for them all to gain a livelihood. Most farmers did not own their own land (as they generally do now) but paid rent to wealthy landlords (known as gentry) for the use of their farms.

Rents were quite high – and out of proportion to what farmers could earn from their produce. The prices they received for cattle and sheep were falling.

The common lands which were once available for the use of all the people in a village were now enclosed – that is they had become the property of the landlords and were leased out to farmers. Labourers (who worked for the farmers) had used the common to graze animals or for gathering firewood, suffered as a result.

If you did not have enough money to support yourself you had to go into one of the new workhouses where conditions were meant to be worse than the worst paid labourer outside.

The farmers also had to pay tithes (a tenth of all their produce each year) to the church, to support the local vicar. But most people who went to religious services regularly went to chapels rather than the church.

They still had to pay, even if they went elsewhere.

In 1836 the way the tithe was collected was changed and it became more of a burden. At the same time a new system of support for the poor was brought in by an act of 1834 and it was becoming established gradually as the riots took place.

Under the new system, if you did not have enough money to support yourself you had to go into one of the new workhouses where conditions were meant to be worse than the worst paid labourer outside.

Families were split up; husbands separated from wives and sisters from brothers.

The farmers thought this a cruel and expensive system. In the past, they had often given food and goods to the poor but now they were expected to pay for building the hated workhouses. This meant paying rates and they had little spare cash.

The trigger for the disturbances was the toll gate system. Roads were especially bad in Wales.

To remedy this, in Wales as elsewhere in Britain, turnpike trusts were established. A number of people (trustees) made up the trust and they improved the roads. In return they were allowed to erect toll gates and collect charges from road users (much like crossing the Severn Bridge now).

Farmers were hard-hit by this as they used the roads to transport lime to their farms to improve the soil. In 1839, a new gate was erected at Efailwen to catch farmers who were evading the tolls.

It was the last straw. Already there were too many toll gates; the market town of Carmarthen was like a fortress with twelve gates around it. The Efailwen gate was destroyed by a large crowd and when it was re-erected, a public meeting was announced ‘for the purpose of considering the necessity of a toll-gate at Efailwen.’

It concluded that there was no need and the gate was destroyed again. Throughout the outbreak there was much good humoured play-acting and a concern to show that there was justice and reason on the side of the rioters.

The name ‘Rebecca’ was that of the mythical leader. ‘She’ had helpers like ‘Charlotte’, Nelly and ‘Miss Cromwell’ and followers (daughters). The name came from the Bible which Welsh chapels goers had learned to read in the previous couple of generations: “And they blessed Rebekah, and said unto her, Thou art our sister, by thou the mother of thousands of millions and let thy seed possess the gate of those that hate them” (Genesis 24 Verse 60).

The toll gates were seen as the property of the gentry (‘those that hate them’) as they were often the trustees of the turnpikes. The gates became a symbol of many different discontents about the land and the church (which was also seen as the church of the gentry).

The rioters wore women’s clothes and blackened their faces, for disguise, but also perhaps to suggest the idea that women were entitled to act to defend their families.

Normally respectable people may have felt that in disguise they were symbolising their community rather then breaking the law as an individual.

Thought there was much discontent in the area there were only a few outbreaks in 1839, including an attack on a new workhouse at Narberth. But in 1842-3, when economic conditions were even worse, the outbreaks swept though the three counties. Soon not a single toll gate was standing there.

Landlords were sent threatening letters to intimidate them into lowering rents. There were violent attacks on individuals who were seen as breaking the ‘people’s law’. ‘I am averse to tyranny and oppression’ was a common remark of the rioters.

Mass meetings were held to raise grievances like tithes, rents, the poor law and many other issues. There was also an attack on the workhouse in Carmarthen in 1843 and other violent actions when shots were fired. Eventually one woman was killed. It is perhaps surprising that there was only one death.

The government sent in troops to try to prevent the outbreaks but they were ineffective. They could be heard coming for miles; the rioters knew the territory much better and could spread false information about where they might strike next.

Troops were often sent on wild goose chases. The Times sent a special correspondent, Thomas Campbell Foster, to cover the riots. He went to meetings and talked to farmers and reported favourably.

In the end the government modified the toll gate system and the poor law to remove some of their worst features and gradually economic conditions improved. More people moved away from the rural areas to the towns.

The railway came into south-west Wales by the late 1840s and made it easier for people to leave. The riots affected the most agricultural areas; if there was nearby industry (as with the lead mines of the northern part of Ceredigion or the slate quarries in Gwynedd) there were no outbreaks. Here there were better chances to earn a living.

The name ‘Rebecca’ lived on. In the 1860s and 70s local people protesting against the sale of fishing rights to outside interests in mid-Wales used the name in their protests, as did farmers in the past fifteen years or so protesting about policies in agriculture.

When the local community bought to right to levy tolls at a surviving toll in Porthmadog in the 1990s, they named it Rebecca and gave the money raised to local charities. But that toll has now ended, though there are still a few of the old tollgates surviving in Wales.

So, with the rights of protesters and the ethics of protesting as a hot topic right now, think of the Rebecca Riots and the force for positive change they produced for the people of Wales centuries ago – maybe such rights shouldn’t be given up so easily?

Add Comment