IF YOU’VE been educated in Wales, you almost certainly know the name Robert Recorde.

You’ll know his history, achievements and legacy.

From primary age to further education, he’ll have been mentioned more than a few times, depending on the subject.

Right?

Because for the man who invented modern mathematics, he’s oddly absent from both our education system and collective knowledge. It’s probably a safe bet that this very article is the first you’ve heard of him.

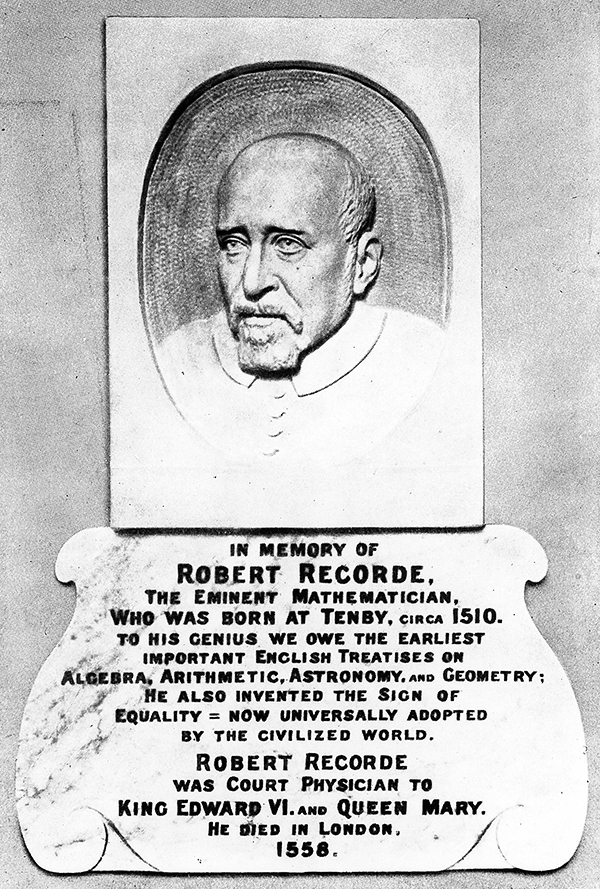

To put this into context, we’re talking about the man who invented the equals symbol (=).

Born in Tenby around 1510, not much is known about the man’s childhood and early life, however he was enrolled on a BA course at the University of Oxford in 1531, and then an MD course in the University of Cambridge.

As well as being a student, Recorde also taught mathematics at both universities until moving to London in either 1547 or 1549.

This is where Recorde’s story begins to get very interesting.

He had the honour of being appointed the comptroller of the Bristol Mint (which has a long and interesting history itself), however in October of 1549 he refused to divert money to English troops who were suppressing a rebellion in the southwest, which led to him being accused of treason by William Herbert.

He refused this as he claimed the orders were not from the King.

His punishment for this act? He was confined for 60 days when the mint was shut down. This, even hundreds of years ago, was viewed as a lenient sentence for such a serious accusation.

However, things did not improve quickly for Recorde from there on out.

In 1551 Recorde was back in favour for he was appointed by the King to be general surveyor of the mines and monies in Ireland. In this capacity he was in charge of silver mines in Wexford and technical supervisor of the Dublin mint.

Silver was important in the King’s financial strategy for Edward VI restored an English coinage of silver. It is interesting that he introduced the silver crown of five shillings which was the first English coin to have a date written in Arabic numerals rather than Roman numerals.

When we say that Recorde was back in favour, it must be understood that his quarrel with Herbert had never been settled and there continued to be animosity between the two.

Herbert became of increasing importance in the country and, in October 1551, was created Baron Herbert of Cardiff and Earl of Pembroke.

The silver mines in Wexford did not become a successful venture for Recorde. There were a great many problems, allegedly all outside his control, which meant that the project never had a chance to succeed.

The technology needed to mine the silver was the subject of a dispute with German miners who operated the mines. In addition the treasury would have needed to invest a great deal of money in the venture before they would have seen a return and this they were not able, or perhaps not willing, to do.

The Earl of Pembroke certainly did not give Recorde support and by 1553, with the mines showing a loss, the project was closed down and Recorde was recalled to England.

Three years later, in 1556, Recorde accused Herbert of malfeasance as commissioner of the minters, which was not a wise move as Herbert was a high ranking man of nobility.

Herbert countered the charges by suing Recorde for libel. The hearing took place in January 1557 and, almost inevitably, the Earl of Pembroke won his action against Recorde.

The award of £1000 which Recorde was ordered to pay to Pembroke was made in February.

Either Recorde could not pay this sum, or he chose not to, for he was imprisoned. If indeed he could not pay it was doubly unfortunate for Recorde since he was owed exactly this amount for his services in Ireland which he had never received.

In fact the £1000 for his work in Ireland was paid to his estate in 1570, but this was not much use to him as, by this time, he had been dead for twelve years.

In the King’s Bench prison in Southwark, he made a will in June 1558 leaving small amounts of money to his four sons and five daughters. He died in the prison, probably no more than a few weeks later.

It’s fair to say Recorde’s life was a mixture of ups and downs, however his legacy lives on today in mathematics. He was renowned not only for the invention of the equals symbol, but also the textbooks he wrote.

These books were meant to be studied from start to finish, in a logical order, with the simple aim of making mathematics easy to digest and learn.

He believed that the education of mathematics should be available to everyone, regardless of their status or wealth, and fought against the elitist attitudes which were common in his peers.

To this end, his textbooks were written in English, rather than Latin or Greek, and used plain colloquial terms.

His experience as a lecturer in both Oxford and Cambridge are not a surprise to anyone who has read his textbooks, as he masterfully guides the reader through the basics, to the intermediate, all the way to the complex.

His work “The Grounde of Artes” which was published in 1543 was advertised as “… the perfect teaching and practice of Arithmeticke etc…” in Recorde’s own words.

This went on to have second and third editions published, with Recorde also writing two more textbooks, Pathwaie to Knowledge and The Castle of Knowledge, in his life.

So, the next time you jot down some sums, think of Robert Recorde, the man from Tenby who made some of it possible.

Add Comment